Introduction to Index Funds

The structure of index funds is central to their role in contemporary investing, as these funds provide a straightforward way to access a wide market segment by replicating the performance of a chosen benchmark. With features like transparency and cost efficiency, index funds are designed to follow indices such as the S&P 500 or MSCI World Index closely. Recognizing how their structure determines benefits and market influence helps investors gauge the true role of index funds in modern portfolios and the financial system.

Index funds have become a cornerstone of investing due to their simplicity and passive approach. This primarily involves tracking an underlying market index, giving investors exposure to a diverse selection of assets, all through a single investment vehicle. These characteristics have fueled the growth and popularity of index funds for both retail and institutional investors. For a historical perspective on the evolution of index funds, readers can refer to the [history of index funds on Investopedia](https://www.investopedia.com/terms/i/indexfund.asp).

Structure and Mechanics of Index Funds

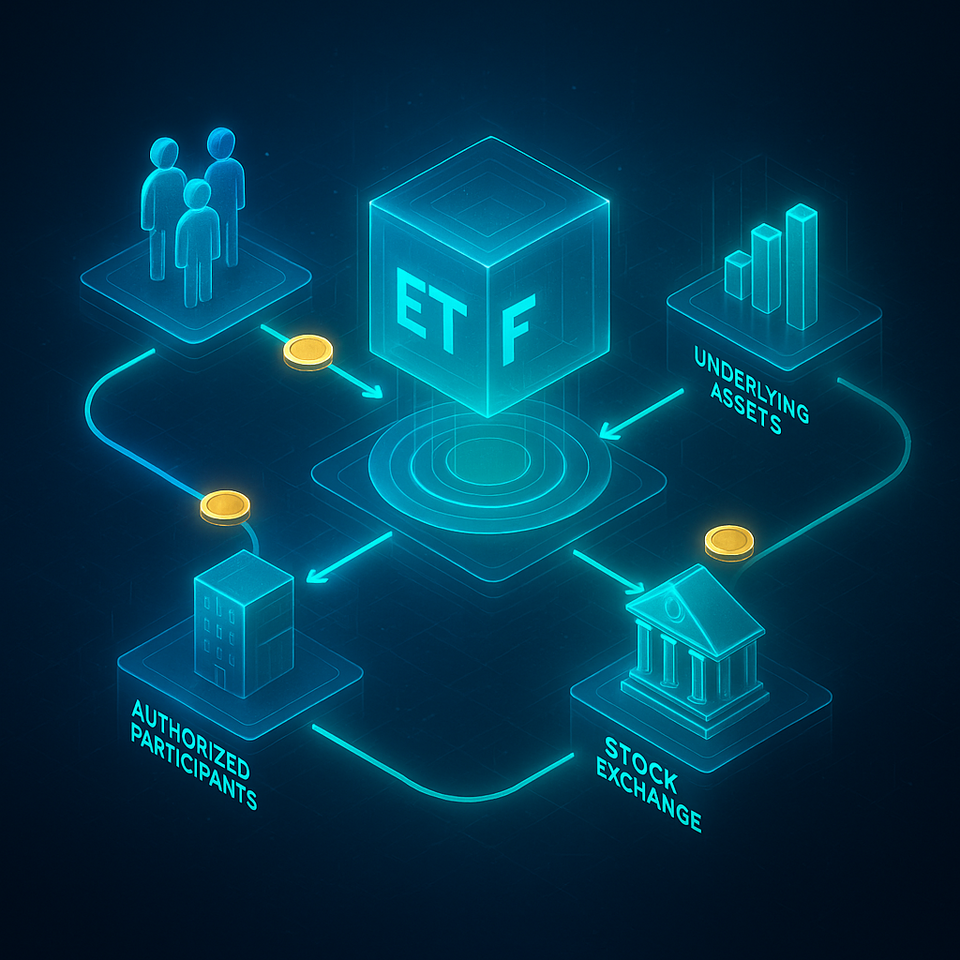

Index funds are created as either mutual funds or exchange-traded funds (ETFs), each aiming to closely mirror the components and weightings of a target market index. Rather than a manager picking individual stocks, the fund composition is governed by the rules of the target index.

A widely used process called full replication involves the fund holding every security in the index, matched to its specific index weighting. In cases where this is impractical, funds may use sampling, holding a subset that statistically parallels the overall index performance. This choice depends on factors like the size of the index, transaction costs, and liquidity.

To maintain close alignment, index funds rebalance portfolios at intervals established by the index provider—this could be quarterly, semi-annually, or otherwise. Portfolio changes, new inclusions, or weight adjustments are executed systematically, minimizing managerial discretion and dramatically reducing portfolio turnover. This operational discipline grants index funds their high transparency and ease of tracking for investors. Holdings are typically disclosed at regular intervals (in many ETFs, daily), and tracking error is reported to help gauge replication efficiency. For more information on index tracking, visit [Morningstar](https://www.morningstar.com/articles/1099676/what-is-an-index-fund).

Types of Index Funds and Benchmark Diversification

The universe of index funds spans a diverse array of asset classes and investment approaches. While equity index funds are the most familiar, tracking indices like the S&P 500, MSCI World, Russell 2000, or technology and healthcare sector indices, the range extends far beyond stocks.

Bond index funds track fixed income markets, like the Bloomberg Barclays Global Aggregate Bond Index, providing broad interest rate and credit risk exposure. Commodity index funds might mirror indices based on metals, agricultural products, or energy resources. Some index funds are designed around factor investing (e.g., value, momentum) or specific regions and countries.

Diversification is a defining strength of index funds: by mirroring broad indices, investors can reduce concentration risk. Customization is also possible, as specialized index funds allow for tilting exposure toward desired sectors, styles, or geographies, addressing specific portfolio construction needs. The proliferation of index-linked products supports strategic asset allocation, as described in guidance from the [U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC)](https://www.investor.gov/introduction-investing/investing-basics/investment-products/mutual-funds-and-exchange-traded-5).

Cost Efficiency and Expense Dynamics

A principal advantage of index funds lies in their cost efficiency when compared to actively managed funds. Since index funds do not require extensive market research or a team of analysts, administrative and management fees (expense ratios) tend to be considerably lower. For example, top S&P 500 index funds can feature annual expense ratios below 0.10%.

Reduced portfolio turnover further minimizes transaction costs and often lessens capital gains tax exposure, directly benefiting investors. Fee transparency is a hallmark—with expense ratios, trading costs, and tracking error clearly articulated in fund documentation. However, investors should account for total cost of ownership, which may include ETF bid-ask spreads, brokerage commissions, or other administrative fees.

Over the long term, the compounding effect of lower expenses can make a significant impact on portfolio growth; various financial models demonstrate this advantage. An overview of index fund cost benefits is available through the [Financial Times](https://www.ft.com/content/2d62b8b8-6e00-11e9-9ff9-8c855179f1c4).

Tracking Error, Liquidity, and Operational Risks

Tracking error describes the difference between the index fund’s returns and those of its underlying benchmark. Several factors contribute to this variance: expense ratios, the use of clinical sampling strategies, rebalancing lags, foreign exchange fluctuations, and trading frictions.

Top-tier index funds seek to minimize tracking error through optimized portfolio construction, detailed risk management frameworks, and technological controls. Liquidity, both at the fund (primary) and in the market (secondary), influences the ease with which investors can enter or exit positions. ETFs offer market-traded liquidity, subject to bid-ask spreads, while mutual funds transact at end-of-day net asset value.

Operational risks in index funds stem from potential replication mistakes, index reconstitution delays, or, in the case of synthetic replication, counterparty exposure. Best practices—such as daily reporting, third-party audits, and clear regulatory oversight—are instituted to reduce these risks for investors. The significance of managing these risks is well articulated by the [European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA)](https://www.esma.europa.eu/press-news/esma-news/esma-publishes-opinion-use-structure-etfs-index-tracking-ucits).

Market Impact, Systemic Considerations, and Criticisms

The rise of index funds has led to profound changes in capital markets, both in breadth and depth. Some critics argue that as capital allocation becomes mechanical, based solely on index weightings, this can cause valuation disconnects, particularly among the largest index constituents. Discussions focus on whether the expansion of passive investing increases correlation among stocks and contributes to potential market instability during periods of stress.

While empirical evidence is mixed, some research suggests index funds may play a stabilizing role through broad-based participation and predictable flows. Regulatory bodies are actively monitoring market dynamics to mitigate any systemic risks as the share of passively managed assets grows. For more on the debate, see the [Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance](https://corpgov.law.harvard.edu/2020/11/23/the-rise-of-index-funds-and-its-impact-on-markets-and-corporate-governance/).

Role of Index Funds in Portfolio Construction

Index funds are favored as core components in both retail and institutional portfolios due to their diversification, cost efficiency, and transparency. They function as the foundation in core-satellite approaches, where the core provides market exposure while satellites allow for higher conviction or alternative strategies.

Portfolio managers leverage index funds to express asset allocation themes, stretch risk budgets, and benchmark performance. Because index funds are rule-based and highly transparent, they enable precise target exposures and facilitate disciplined portfolio management. Combinations with actively managed funds or alternative assets allow for tailored solutions to meet risk and return objectives.

Regulatory Environment and Disclosure Practices

Strict regulatory frameworks—such as those enforced by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) or the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA)—dictate comprehensive disclosure and transparency. Fund issuers must clearly outline investment processes, risks, costs, and shareholder voting arrangements in prospectuses and other key documents.

For ETFs, additional requirements apply around intraday pricing, redemption mechanisms, and transparency of holdings, often exceeding those expected of traditional mutual funds. Ongoing regulatory focus aims to ensure market stability, protect investor interests, and support confidence in the integrity of index-linked investments. Industry standards and routine auditing reinforce reliable performance reporting, while investor education initiatives help clarify product differences and risks.

Historical Context and Evolution of Index Funds

Index funds originated in the 1970s with the launch of the first S&P 500 index fund, marking a profound shift from active management to broad-based market exposure. Their popularity grew with the development of new benchmarks, international diversification, and the advent of ETFs in the 1990s. The shift was driven by academic research suggesting the difficulty of consistently outperforming the market net of fees. Over decades, the structure of index funds stayed the same, but technological innovation and regulatory changes improved efficiency, transparency, and access. For more background, visit [Wikipedia – Index Fund](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Index_fund).

Comparisons and Contemporary Issues

When comparing index funds and actively managed funds, numerous studies show that passive strategies often outperform after expenses over extended periods. However, index funds may be limited by the universe of available benchmarks and could be less responsive to sudden market shifts. On the other hand, active management offers flexibility but at a higher cost and with no guarantee of excess returns.

Recent trends include the launch of ESG (Environmental, Social, Governance) index funds, further expanding investor choice and aligning with evolving preferences. Regulators, however, are increasingly attentive to issues such as greenwashing or complexity in index methodologies.

Conclusion

Index funds provide reliable market exposure through clear structure and cost efficiency. Their transparency, regulatory frameworks, and diversification benefits have established them as essential for modern portfolio construction. As financial markets evolve, the structure of index funds will continue guiding their performance, regulation, and role in investment strategies.