Introduction to a Modern Investment Revolution

Exchange Traded Funds (ETFs) are pivotal instruments in modern finance. They offer investors accessible, liquid, and diversified exposure to a vast range of markets. Essentially, ETFs are pooled investment vehicles with shares that trade on stock exchanges, much like traditional stocks. Since their emergence in the 1990s, these funds have significantly changed investment practices for both large institutions and individual retail participants. With a unique structure that enables efficient portfolio construction and transparent asset exposure, ETFs have become integral in achieving broad or highly targeted diversification. Consequently, grasping the details of how ETFs function is essential for understanding their evolving and critical role in global capital markets.

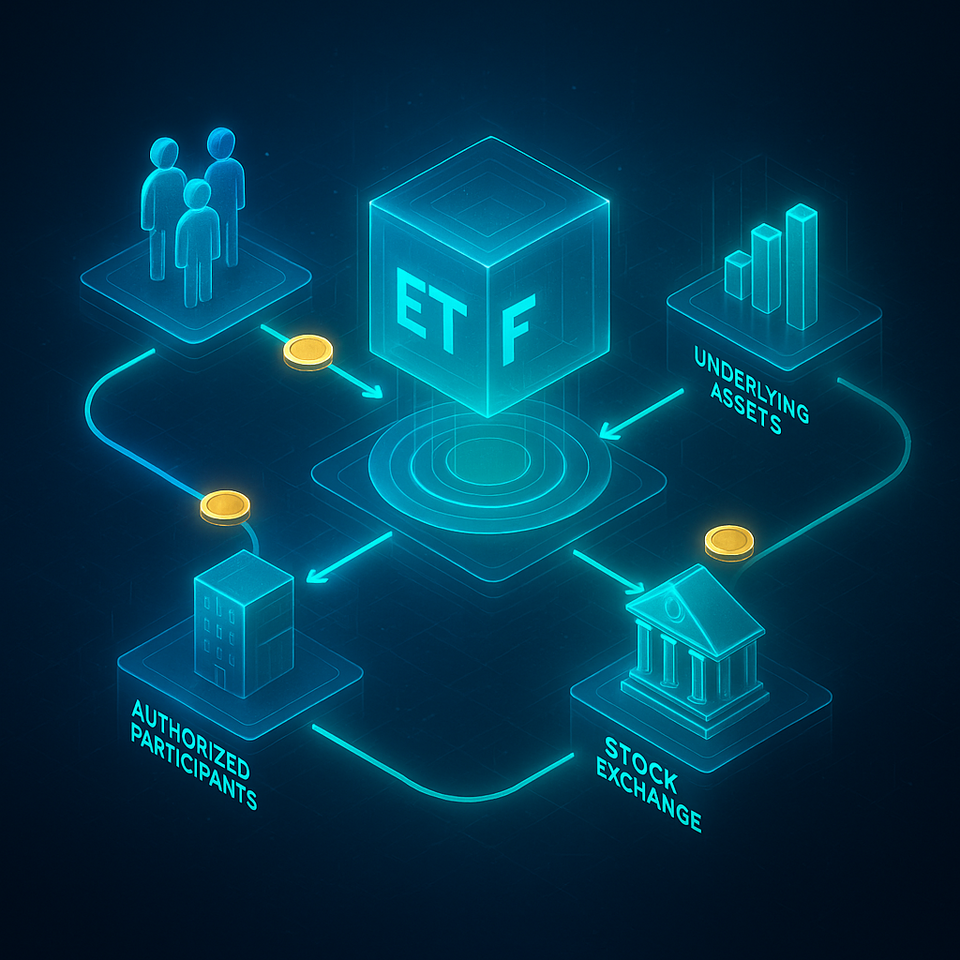

The Unique Structure and Mechanisms of ETFs

The open-end structure of ETFs clearly distinguishes them from other investment vehicles. While sponsors may set up ETFs as unit investment trusts or mutual funds, their main difference is the ability for their shares to be bought and sold continuously throughout market hours at prevailing market prices. This contrasts sharply with traditional mutual funds, which only settle transactions once per day at the net asset value (NAV).

Creation and redemption are the core mechanisms that ensure ETFs work efficiently. Authorized participants (APs)—which are large financial institutions—facilitate this process. They engage in in-kind exchanges, meaning they can deliver a specific basket of underlying securities to the ETF sponsor and, in return, receive a block of new ETF shares. Conversely, they can redeem ETF shares to receive the underlying securities. This continuous process keeps an ETF’s market price closely aligned with its NAV, significantly reducing pricing discrepancies and ensuring fair value for investors.

Furthermore, ETFs can be physically backed, meaning they hold the actual shares or assets of the index they track. Alternatively, some employ synthetic replication, using swap contracts and other derivatives to deliver the index’s return without owning the underlying assets. Most ETF sponsors enhance transparency by disclosing their fund’s complete portfolio holdings daily on their website, a feature investors highly value.

The Diverse World of ETFs and Market Offerings

The ETF market offers a diverse and ever-expanding array of structures and strategies to meet nearly any investment goal.

- Broad Market ETFs: These funds track major benchmarks like the S&P 500 or the MSCI World index. As a result, they enable investors to achieve instant diversification across large segments of the equity market with a single transaction.

- Sector ETFs: These are designed for investors seeking concentrated exposure to specific industries, such as technology, healthcare, financial services, or energy.

- Bond ETFs: These funds provide liquidity and real-time pricing for access to various fixed-income markets, including government, municipal, or corporate bonds.

- International and Emerging Market ETFs: These offer investors straightforward exposure to non-domestic equities and fixed-income instruments, allowing for global diversification in one trade.

- Commodity & Thematic ETFs: These funds track physical resources such as gold, oil, or agricultural goods. Thematic ETFs, on the other hand, focus on emerging investment trends like green energy, artificial intelligence, or digital innovation.

- Leveraged and Inverse ETFs: These are complex products intended for sophisticated traders. They use derivatives to multiply the daily returns of an index or to profit from falling markets. However, these instruments carry significantly higher risk due to the effects of daily compounding and are not recommended for long-term, passive investors.

The Core Benefits of Investing in ETFs

ETFs provide several major advantages, making them a favored choice for both individual and institutional investors.

- Diversification: A single ETF share typically represents a stake in a portfolio of dozens or even hundreds of securities, which dramatically reduces the risk associated with any single stock or asset.

- Liquidity: Investors can trade ETF shares throughout the day at market prices, offering flexibility that mutual funds, which only transact at the end-of-day NAV, cannot match.

- Cost Efficiency: Passive ETFs, which aim to replicate an index, often charge substantially lower management fees (expense ratios) than actively managed funds.

- Tax Efficiency: In certain jurisdictions like the United States, the in-kind creation and redemption process helps minimize the distribution of taxable capital gains to shareholders, making them a more tax-efficient vehicle.

- Transparency: Daily portfolio disclosures allow investors to know exactly what assets their fund holds, enabling them to monitor exposures and risks in near real-time.

- Flexible Market Exposure: Investors can employ ETFs for a wide range of strategies, including tactical asset allocation, sector rotation, hedging, or building core-satellite portfolios.

Risks and Considerations Associated with ETFs

Despite their many strengths, investors must remain mindful of several risks inherent in ETFs.

- Market Risk: The value of ETF shares moves in tandem with their underlying securities. Therefore, they are fully subject to market volatility and can lose value.

- Liquidity Risk: Some ETFs track less-liquid assets, such as niche bonds or micro-cap stocks. This can lead to wider bid-ask spreads and difficulty transacting, particularly during stressful market conditions.

- Tracking Error: A discrepancy can arise between an ETF’s performance and its reference index. Fees, transaction costs, and imperfect replication strategies can all contribute to this tracking error.

- Premium/Discount Risk: ETF shares may trade at a market price that is slightly above (a premium) or below (a discount) their NAV, especially for thinly traded or less transparent funds.

- Complex Product Risk: Leveraged and synthetic ETFs involve advanced derivatives and carry heightened dangers, including counterparty risk (if the swap provider defaults) and compounding risk (which can cause long-term returns to deviate significantly from the index’s performance).

The Regulatory Framework and Oversight of ETFs

Regulatory oversight of ETFs aims to safeguard investors and ensure orderly, transparent markets. In the United States, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) primarily governs ETFs under the Investment Company Act of 1940. The SEC enforces strict requirements for portfolio transparency, diversification, and mandatory disclosures. ETFs that utilize significant leverage or derivatives face even heightened scrutiny and additional regulatory requirements to protect investors from undue risk.

In Europe, the UCITS (Undertakings for Collective Investment in Transferable Securities) directive provides a harmonized legal framework. This framework targets diversification, risk control, and liquidity, creating a regulatory “passport” that allows an ETF approved in one EU country to be sold across the continent. Despite these efforts, some discrepancies remain between jurisdictions. As ETFs become key vehicles in global capital flows, international cooperation between regulators continues to intensify.

The Widespread Impact of ETFs on Financial Markets

The exponential growth of ETFs has reshaped several dimensions of the financial markets.

- Liquidity Provision: ETF shares often trade with high volume and frequency, in many cases boosting the overall liquidity and market depth of their underlying securities.

- Fee Compression: Intense competition between ETF providers has driven down investment costs across the entire asset management industry, broadening investor access to new and affordable strategies.

- Price Discovery: ETFs promote more efficient price formation and capital allocation across various market segments.

- Market Risk Transmission: Conversely, some research suggests that the interconnected nature of ETFs may accelerate volatility or transmit shocks between asset classes during systemic crises. Policymakers and central banks actively monitor the systemic role of ETFs, particularly regarding market-making and their behavior in periods of stress.

The Future of the ETF Industry

Financial innovation, shifting investor demands, and evolving regulatory frameworks will shape the future trajectory of the ETF industry. New ETF products continue to emerge, covering areas like environmental, social, and governance (ESG) investing, digital assets such as cryptocurrencies, and direct indexing solutions that were traditionally reserved for institutional allocators.

Furthermore, active ETFs are gaining significant traction as asset managers seek to combine the benefits of intraday liquidity with tailored, professional investment management. Technological advances are also bringing fractional trading and digital distribution platforms to mainstream users, which reduces minimum investment hurdles and enhances retail participation. As the asset management industry remains highly competitive, fee pressure will continue, driving providers to maximize efficiency and improve investor outcomes.

Conclusion

Exchange Traded Funds have become essential instruments for both individual and institutional investors. They offer efficient and affordable access to a wide spectrum of global markets. Their transparent structure, daily liquidity, and typically low costs contribute to their growing preference worldwide. However, recognizing the risks and regulatory shifts surrounding ETFs is vital for making informed investment decisions. As financial markets continue to develop, ETFs are certain to remain at the forefront of innovation