Introduction to Exchange-Traded Funds (ETFs)

Exchange-Traded Funds ETFs have become a cornerstone of modern investing by offering access to diversified portfolios through a flexible and transparent mechanism. Exchange-Traded Funds ETFs are listed investment funds traded on stock exchanges, much like individual stocks, and are structured to reflect various indexes, commodities, sectors, or asset classes. Their rise since the 1990s has greatly influenced investment strategies for both institutional and retail investors, who now use ETFs not only for long-term portfolio building, but for hedging and tactical allocation as well. The popularity of ETFs can be traced to their cost efficiency, transparency, liquidity, and ease of access.

Unlike mutual funds, which are transacted only at the end of the trading day, ETFs are bought and sold throughout market hours at real-time prices, acting as a bridge between the flexibility of equities and the diversification of funds. This trading model enhances overall market liquidity and provides investors with adaptable vehicles for risk management and exposure control (source: Investopedia).

ETFs: Mechanism and Structural Components

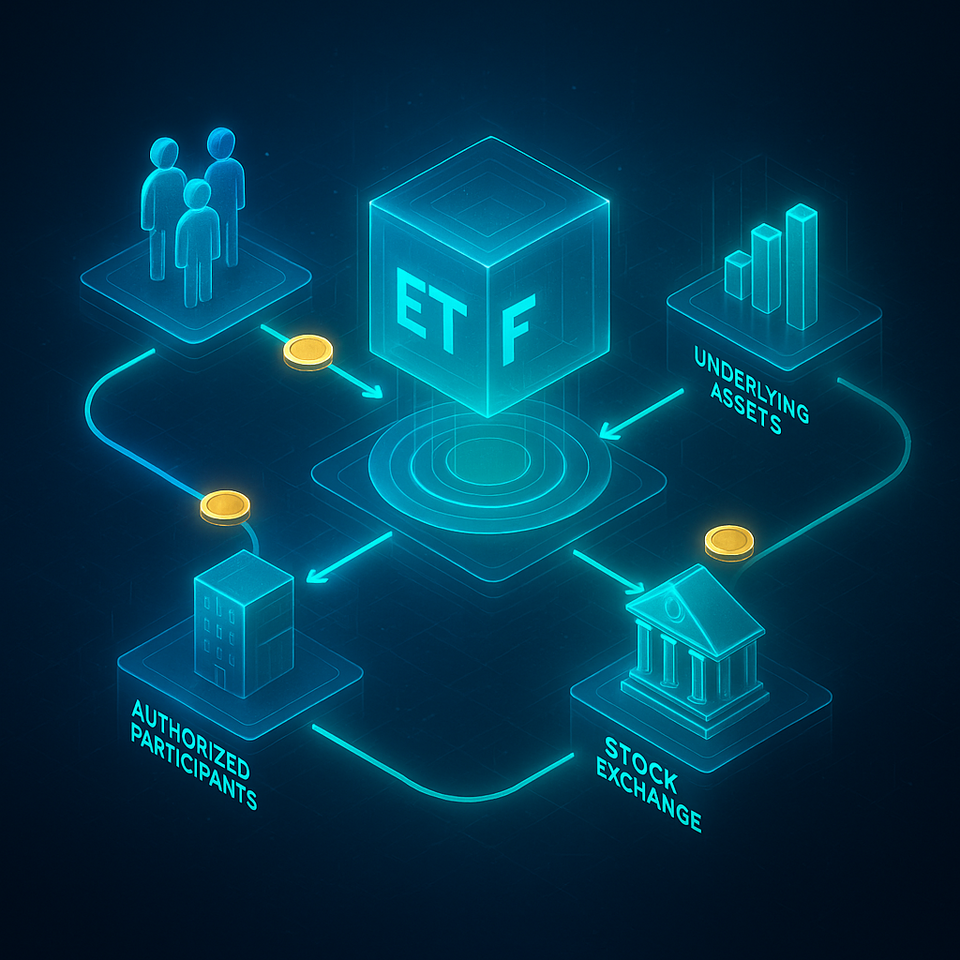

At the heart of an ETF is a portfolio of underlying assets—such as stocks, bonds, or commodities—which are managed to track a specified index or match an investment strategy. ETFs issue shares that are listed and traded in secondary markets. The underlying assets are held by a custodian to ensure investor protection and structural integrity.

A key aspect of ETF mechanics is the role of authorized participants (APs) — large institutions responsible for creating and redeeming ETF shares. When demand rises, APs exchange baskets of securities for ETF units, a process called “creation.” Redemption, conversely, lets APs deliver ETF shares in exchange for baskets of underlying securities. This structure is critical to keeping ETF prices near their net asset values (NAV) through arbitrage opportunities.

Transparency is emphasized by frequent disclosure of holdings (often daily), which allows investors to verify tracking accuracy and assess any deviations from their benchmarks. While the majority of ETFs are passively managed, tracking established indexes like the S&P 500, active ETFs have emerged, offering additional choice for investors seeking alpha (source: SEC.gov).

Liquidity, Trading, and Pricing Dynamics

Liquidity in ETFs is influenced by both the trading volume on exchanges and the liquidity of the underlying assets. Some ETFs, especially those tracking broad markets, exhibit robust trading, while those covering niche sectors may trade less frequently. Nonetheless, the ability of APs and market makers to create or redeem shares helps maintain price efficiency, as discrepancies between market price and NAV are swiftly arbitraged away.

This built-in arbitrage mechanism ensures that even less actively traded ETFs can reflect the value of their contents. Investors can use diverse order types, such as market, limit, or stop orders, to fine-tune trades—providing an advantage over traditional mutual funds. Real-time pricing and transparency support effective risk management for both retail and institutional investors.

Types of ETFs and Segmentation by Asset Class

ETFs can provide exposure to almost any asset class, serving a wide breadth of investor preferences:

- Equity ETFs: Track major stock indexes (e.g., S&P 500), sector themes, or geographic regions.

- Fixed Income ETFs: Replicate government bond, corporate bond, or municipal bond markets for efficient debt exposure.

- Commodity ETFs: Provide access to physical commodities like gold, oil, or agriculture, or use derivatives for exposure.

- Currency ETFs: Track baskets of foreign currencies, enabling both speculation and hedging of FX risk.

- Thematic and Niche ETFs: Focus on industries such as technology or renewable energy, or follow specific investment trends.

- Leveraged and Inverse ETFs: Utilize derivatives to amplify or invert benchmark returns, primarily for experienced traders.

Most individual investors use broad-based equity or bond ETFs as core holdings, while advanced users may employ leveraged or inverse ETFs for tactical purposes. The suitability of each ETF depends on the investor’s risk tolerance and strategy (source: MSCI).

Efficiency and Cost Structure of ETFs

A major advantage of Exchange-Traded Funds ETFs is cost efficiency. Passive ETFs, by design, require less portfolio turnover and analysis than actively managed funds, resulting in lower expense ratios. Many ETFs have expense ratios far below the industry average for mutual funds. Commission-free trading on many brokerage platforms has further amplified the cost benefits for investors.

Another aspect is tax efficiency: the in-kind creation and redemption process often avoids the need to sell securities in the open market, minimizing capital gains distributions to shareholders. Despite these structural tax advantages, investors may still face trading commissions, bid-ask spreads, and local tax rules that can affect net returns.

Opaque or niche ETFs may come with higher costs due to the complexity of tracking less liquid assets or specialized markets. Conducting a full cost assessment before investing—taking into account explicit and implicit costs (like bid-ask spreads)—remains important for all investors.

Risks Associated with ETFs

ETFs share common financial market risks, including market risk, liquidity risk, and tracking error. Market risk stems from the price volatility of the underlying securities or markets being tracked. Tracking error occurs when an ETF fails to align its performance precisely with its benchmark, which may result from fund fees, rebalancing, or imperfect replication.

Liquidity risk is significantly relevant for ETFs that hold thinly traded or illiquid underlying assets. Even with the arbitrage mechanism in place, sharp market dislocations or disruptions in the underlying markets may challenge ETF liquidity. Leveraged and inverse ETFs present additional complexity and risk, as the compounding of returns and use of derivatives can result in large divergences from expected behavior over time.

Regulatory scrutiny, particularly by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission and similar bodies globally, continues to examine the systemic implications of ETF growth, especially as more synthetic and complex ETF products enter the market (source: ESMA).

Role of ETFs in Portfolio Construction

The accessibility of Exchange-Traded Funds ETFs has reshaped investment portfolio construction for individuals and institutions alike. Investors can quickly access diversified market exposures or construct multi-asset strategies using only a few ETF positions. A popular technique involves a “core-satellite” model, where broad-based ETFs form the core allocation, and thematic or sector ETFs supplement as satellites.

Robo-advisors and digital portfolio platforms frequently use ETFs for their liquidity, transparency, and low-cost profile, making sophisticated asset allocation strategies available to a broad audience. For institutions, ETFs assist with rapid tactical moves and strategic rebalancing. The proliferation of ETFs also supports ESG and socially responsible investment mandates, giving investors targeted access to values-based criteria.

Market Impact and Regulatory Considerations

The scale and breadth of Exchange-Traded Funds ETFs have materially altered global market structure. ETF growth has increased competition, reduced transaction costs, and deepened secondary market liquidity. Research suggests ETFs support greater price efficiency in underlying securities by enabling swift arbitrage and rapid portfolio adjustments.

However, concerns remain around market stress. Some observers have questioned whether ETFs could exacerbate volatility in stressed markets, particularly for less liquid asset classes. Regulators address these issues through enhanced disclosure, liquidity standards, and reporting requirements to ensure orderly markets and investor protection. Ongoing dialogue among regulators, fund sponsors, and industry participants aims to address the complexities as ETF products become increasingly diverse and globally interconnected.

Conclusion

Exchange-Traded Funds ETFs have established themselves as fundamental instruments in portfolio construction thanks to their combination of flexibility, transparency, and market liquidity. Their cost-effectiveness and ease of access are key drivers of their widespread appeal. Investors benefit from their diverse exposures and simplicity, but an understanding of associated risks remains essential as ETFs continue to shape market practices and investment management.